FINDING PARADISE IN A HUNTING CAMP

* Turning Poachers to Protectors *

Journal of the Southwestern Anthropological Association

Vol.

38, Issue 3, January, 1998

Dr. Anthony L. Rose

The Biosynergy Institute, USA

This is a personal account of life in a west African bushmeat hunting camp from the perspective of a wildlife conservationist who believes that people and nature can be redeemed, if given opportunities to pursue their mutually synergistic ideals.This effort was supported in part by a small gift from The Bellerive Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland.

See Travel Document Systems for present travel conditions and entry requirements in Cameroon.

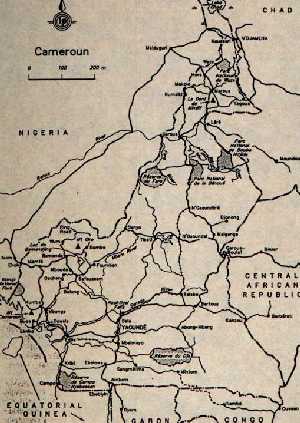

I went to Cameroon's Eastern Province in May, 1997, with a complex agenda. My prime goal was to experience life in the bush with commercial hunters so I might assess the potential for converting some of them to protectors of wildlife. A year earlier I had participated in a conference with officials from the Cameroon Ministry of Environment and Forests (MINEF) at which the factors effecting the growing "bushmeat crisis" were discussed. My role as an applied social psychologist and developer was to analyze the crisis and to conceive innovative solutions (Rose, 1996). Subsequent meetings and correspondence with scores of independent experts affirmed the assertions of local officials that conservation biology projects had failed in this arena. To me it seemed obvious that to alter a convoluted matrix of human values and to control a multi-million dollar commercial enterprise was the job of social scientists and business people. From the elite gentry in national and provincial capitals paying top dollar for elephant steak to the itinerant hunters snaring blue duiker and shooting apes for logging camp workers, this is a human affair.

|

On Thursday May 8th I arrived in Douala, Cameroon's largest city and one of the principle sea ports in western Africa. The next morning I took a bus to the national capital of Yaounde. There I met with my colleague, Dr. Kerry Bowman, a social worker and bioethicist from University of Toronto, whom I had recruited to work with me on the project. Kerry had stopped in Yaounde on return from lecturing in Cape Town. He had been interviewing hunters, traders, and consumers of bushmeat for nearly a week and was anxious to get to the bush as his time was running short. Joseph Melloh arrived early that afternoon and we prepared to leave for the Eastern Province right away. Joseph would spend nearly two weeks with me traveling from one end of Cameroon to the other, riding in bush taxis and logging lorries, sleeping in flop houses and fancy hotels, living in hunting camps and timber towns.

|

"Isn't that fellow in danger, hanging out here with all this drinking going on?" I asked.

"Why should he be in danger?" replied Joseph. "If anyone hurt him they would be beaten on the spot and put in jail. The worst crime is to do harm to someone like that. We take care of such men."

"What if he were a white man?" asked Kerry.

"We must look after all white men. They are guests. We are not supposed to let any harm come to you."

My Canadian friend and I exchanged glances. "That's much better than in North America. Strangers and crazy people are given a hard time where we live," said Kerry.

"If I came to your country, would it be hard for me?" Joseph asked?

"Not if you stayed with Kerry or me. But alone you would have a very rough time," I replied.

"One day I would like to come stay with you in America," mused Joseph.

The rest of the evening passed with little event till we returned to our six dollar rooms in the town's most popular disco and brothel. Loud music and raucous party goers crashed through the halls till the wee hours. I was exhausted when we took off early Sunday in another bush taxi down another red clay highway lined with tall trees. In three more hours we reached Kagnol, the western style logging camp in the heart of the SEBC concession. After leaving a card for the MINEF officer, we continued a half hour on an abandoned logging road through increasingly dense forest to the hunting camp called Tokasa.

It was midday and the overhead sun intensified the colors of clay, vine, and leaf. We pulled our gear from the trunk, paid the driver, and watched the faded beige Toyota turn and disappear. It was then I saw the butterflies -- small streams and clouds of yellow, blue, red, and green floating crystals that spun round us. On a hill above the grass covered berm were four small huts woven of poles and thatch. Behind them, huge towering trees, hanging vines, moss, a dark forest wall of wood and shadows, tinted emerald and brushed with fluttering white wings, a red flower, streaks of gilded light. And all around -- silence. Utter silence. I sighed. And then the forest sang again. A bird. Crickets. Bees, and the rustle of wind high in the canopy. Joseph helped me put my gear in the hut. I sat on a bench in the small verandah and stared at the forest. An unexpected and welcome paradise.

I spent seven of the next ten days and nights at Tokasa camp. Windfalls had blocked the road a few kilometers beyond us with immovable logs. No other cars came. Further on were five small hunting camps; ours was closest to the main road. To get from our site to the auberge in Kagnol was a 2 hour walk through forest. This meant that everyone passing by in either direction stopped at Tokasa to drop their packs, rest, and visit. On the third day Kerry had to hike out and hitch to Yaounde, to catch a plane back to Cape Town. I recalled gratefully what Joseph had said about caring for guests and strangers, now that I was the only white man in the forest. Joseph's wife and child arrived, along with other men and families. The camp began to fill up. Hunters, trappers, bushmeat traders, gatherers of fruit, honey, medicinal plants -- more than 40 people altogether came to stop and sleep in Tokasa camp while I was there.

|

Most were Bantu men from towns and villages in the Eastern Province who were moving back into the forest at the start of the rainy season. They came with rented guns, a handful of cartridges, and material for snares and traps -- enough to get them sufficient meat to sell at market for a living and small profit to save or to spend on their families back home. From sunup to sundown these hard-working men would trudge up to my hut to shake hands with the odd gray haired American who had come to live in their midst.

Joseph's introduction set the stage -- "my friend Dr. Anthony is here to find out how we live and see if we can make a better life." Some were shy and said little. Most were glad to see me, and many were visibly elated to find that a white man could take them as they are, without judgment. Many were forthcoming.

Etienne had come to hunt for the first time a few weeks earlier. After his mother died he and his younger brothers could not make ends meet. He had joined agemates from his village in hopes of earning some money. While we talked his compatriots showed me their catch. One red duiker and two blue ones, two monkeys -- all fresh shot that morning. They also had two porcupine and two duiker smoked from the day before. Etienne did not have a gun, but his friends would teach him to use theirs. At the end of the season he hoped to have saved enough to return home and expand the family farm. He was more bold than the others, and asked if I might get him a small camera -- he would like to be a photographer.

I returned from a walk in the forest late one afternoon to find a more experienced hunter seated by the fire in front of my hut. Marcel held a relic of a gun in one hand and pointed to the meat he had laid out to smoke on the rack above my fire. Two monkeys and a red duiker shot with the gun, two porcupines caught in snares. "A poor day's catch" he explained. Marcel had stopped to rest on his way to the logging camp. He heard that an uncle had died in his village and he must return for the funeral. The sale of the meat in Kagnol would bring him enough cash to pay transit there and back on a lorry -- about $10. I asked if he had ever hunted an ape. He said that 2 weeks earlier he shot a chimpanzee. It was too heavy for him to bring out, so he and some other hunters ate the feet, hands and innards; then sold the larger portions, back, legs and arms, for $17. "Will you be a hunter all your life?" I asked. "No, of course not." Marcel hopes to save enough capital to open a shop in his village. But it will take another 2 years or more, with luck.

Joseph learned that while he was in Yaounde meeting me, a gorilla was shot and butchered about 15 kilometers down the road beyond our camp. It's carcass had lain right here in front of my hut, before being carted out to the road and shipped to Bertoua, the provincial capital.

"My friend has shot many gorillas, if you want to meet him. But we will need a car," Joseph offered.

A week later we got a ride with a writer from Stern Magazine. We drove the 50 kilometers on a relatively busy dirt road to an upscale encampment with houses made of mud and wood. In a new half-built five room house a handsome bright-eyed young man named "Davide" greeted us. We examined three gorilla skulls collected months earlier. He pointed out the nine holes that represent all nine lead balls of the Chevrotine cartridge. "This was a perfect shot."

|

"Of course not. It is dangerous and very hard work. But if I find them, I must use the gun that my patron has given me for its purpose," he replied. Davide expects to save money and quit the hunting life one day.

"He is a good man. Very trustworthy and honest. I would like to take him with me to help protect the gorillas and chimpanzees in the forest," said Joseph.

Earlier I had asked Joseph when he last killed a gorilla. "I have shot one gorilla in the year since I saw you," he replied. "I know that you and the others do not want me to hunt them anymore. I no longer have a gun, and have begun to grow the crops." But he explained that he has now reached the end of the rope.

"The month of May is time to finish my planting so the corn and casaba will be here in the fall. In July my family will gather fruit and honey to prepare and sell. But for June we do not have enough to live on. That is why I must begin to hunt again."

I asked him how much money he needs. He calculated and replied that $120 would get him through the next six weeks. After that the fruit should come in and tide him over till autumn harvest. I figure in six weeks Joseph could kill a dozen great apes, as many as his young friend Davide.

"Don't hunt, Joseph. We will make a contract," I said. "If you will keep a journal in which you record one accomplishment you have made each day, and send me copies every 2 or 3 months, then I will give you the money you need to stay away from the hunt and will help you start to protect the endangered animals."

Joseph was visibly pleased. "I will get the paper and the pen and begin today," he declared.

After making our agreement I felt a strong sense of relief. For days I had been struggling with a difficult conundrum. To help the apes required trusting the ape killers. As a professional from North America I needed reasonable proof that Joseph would not use this money to rent a gun, buy cartridges, and return to the hunt. As a person in the rain forest I had the man's word, and I knew his word was good as gold.

Joseph and I left Tokasa camp by different routes and met up again in Yaounde near the end of my sojourn. He then accompanied me by bus back to Douala and down to the resort town of Limbe. During those three days out of the forest a different man began to emerge. A worldly man, at once confident and cautious, open and honest, and quite insightful about his place and potential in this difficult world. At the Atlantic Hotel in Limbe I video-taped a long interview with Joseph the ex-gorilla hunter.

Joseph the boy had been slated to attend a technical school, but the funds were used instead to send his brother to college. After high school he found himself adrift, and took a variety of jobs, from house boy in Limbe to milliner and restaurant manager in Yaounde. He traveled north to work in Nigeria, then returned to Yaounde to study French, and at age 28 he moved to the Eastern Province where he could start afresh in Cameroon's frontier state. There he married a B'aka pygmy woman, adapting to yet another language and culture. As journalists and TV crews began reporting the exploitation of flora and fauna in east Cameroon, Joseph with his relevant skills and knowledge was discovered to be a valuable resource person. Now he was proving himself to have yet another set of talents, working as my private tour guide.

We talked for hours and days about life in Cameroon and life in the bush. In the end I was convinced that while Joseph had an exceptional mix of competencies, he was the tip of an iceberg. There were at least a dozen other bushmeat hunters back in the SEBC concession who had sufficient will and ability to serve the conservation effort. As I watched Joseph's bus rumble out of Limbe town, I was convinced that what had been done in other African countries converting poachers to protectors (e.g.: Owens & Owens, 1993) could also be accomplished in Cameroon. Joseph Melloh could be the first of many.

Now there is a man in the rain forest of eastern Cameroon who is diligently recording the events that matter to him most, focusing on what brings a sense of achievement to his life, and striving in the face of odds to get through this hunting season and this year without killing apes or any other living being. I received a package in the mail from Joseph in August. He had survived without hunting so far. He also built an addition on his house and continued the planting in the village of Bordeaux where his family lives. His most intriguing achievement from my viewpoint is illustrated in these four journal entries:

- 1 June: "I have left Bordeaux to visit Davide in his camp."

- 2 June: "Davide and I have gone to the forest where he used to hunt and we have met two groups of gorillas which I have asked him not to shoot. He accepted not to kill them. I have spent the night there with him in the forest. He only got some monkey for his market."

- 3 June: "Davide and I have passed another night in the forest."

- 4 June: "I have left Davide's camp and I am with my family in Bordeaux."

But despite his preliminary success in the wildlife protection arena, Joseph reported that his family had failed in their farming program. The fruit and honey was scarce: not enough money had been made to last 'till the harvest. With donations from friends at CSULA and LA Zoo, Biosynergy Institute (BSI) has sent another $400 to Joseph along with a contract that defines the aims of our additional investment.

Aim 1) To encourage Joseph and his family to maintain their health and well-being during the period of his transition into a new life-career.

Aim 2) To guide Joseph in obtaining the training and employment that will transform his skill and understanding of Cameroon wildlife into assets for wildlife protection, education, and touring.

Aim 3) To provide Dr. Rose with reliable information so that BSI and its donors can effectively audit and support the needs and accomplishments of Joseph and his family in this transition.

Aim 4) To assure that Joseph and his family refrain from the hunting, trapping, purchase, and eating of any and all animals whose populations are vulnerable to extinction, and that they focus their energy and resources on the new activities and accomplishments they must make in order to serve the wildlife conservation effort.

While the money and contract were in transit to Cameroon a phone call from the government Wildlife Chief in Bertoua came through to me. The official reported that his rangers had arrested and were prosecuting a group of men and women caught transporting tons of elephant, gorilla, and chimpanzee meat. He also told me he had been in touch with Joseph and urged me to support the man who was "a precious instrument to provide information on the hunting situation deep in the forest in SEBC." When I replied that money was on the way, the Chief was greatly pleased and offered to help in any way he could with the program to train and re-employ Joseph.

Unfortunately that program is easier conceived than accomplished. A French logging executive has offered sections of his new million acre timber concession as location for a wildlife tourist site, if Joseph can develop a working relationship with local residents and establish a safe protected area. Resourceful as he is, Joseph needs professional and financial support for such a project. An endowment for him and his family for at least the next 2 years is fundamental. I'm confident this alone would keep Joseph out of the bushmeat business. But to find and hire the professionals with relevant expertise to train Joseph and other hunters and to develop and establish conservation related work for them in Cameroon is the critical path.

Thus far we have had many leads but no closure. Traditional donors praise our pursuits, but spend their money on their familiar old projects. Professional talent goes where the money is -- the most devoted among us must make a living. Government and private agencies in places like Cameroon are so poorly funded they cannot perform their assigned duties, let alone start new programs, without support from outsiders. Ironically, this whole effort could be launched for the price of one of the luxury automobiles on sale in a car lot a few blocks from my house. Five BMWs could put scores of hunters to work in wildlife conservation projects that would help dozens of local economies and save many thousands of endangered animals in the rain forests of Cameroon.

I went to Cameroon's Eastern Province to experience life in the bush with commercial hunters. I came back convinced that these men and the socio-economic systems in which they are caught can be changed in ways that will restore and enrich the people and the natural heritage. My commitment to facilitate this change remains strong -- hopefully the will can produce the way. The next letter from Joseph should be in the mail now, perhaps announcing the birth of his new child and indicating that he has managed to keep his promise to avoid hunting for another two months. Today I will talk with my children to decide how much money our family will send to Joseph as a gift for Christmas. Tomorrow I will send this story to friends asking for ideas and support.

In Tokasa Camp one balmy afternoon I handed Joseph the video camera and asked him to interview me. He was delighted, and quickly got right to the point.

"Mr. Anthony, are you interested in me because I am a hunter or because you want to improve my life," he asked.

I thought hard before answering. "When I first came here to Tokasa Camp it was so I could learn about the hunters, and see if I could help them to make a better life for themselves, and for the wild animals that live here. But now, after living with you for all these days, it has become a personal thing for me. Now I want to help you Joseph, and your family, to make a better life."

I went to Cameroon as a conservationist, and came back as a friend.

References:

Owens, D, and Owens, M. (1992) The Eye of the Elephant. Houghton-Mifflin, New York.

Rose, A. L. (1996a) The African forest bushmeat crisis. African Primates, 2 (1): 32-34.

Rose, A. L. (1996b) The African great ape bushmeat crisis. Pan African News, 3 (2): 1-6.

Readers are invited to contribute to the Biosynergy Institute's Bushmeat Project. Support for the "Poachers-to-Protectors Program" will help Joseph and other men and women give up the bushmeat business and devote themselves to saving great apes and to protecting the natural and cultural heritage of Cameroon. Write or e-mail us to discuss how you can help.

Joseph has since written to say that, although still in financial difficulty, he has not killed any great apes, and has had some success persuading Davide not to kill them as well.Dr. Rose is writing a book about the great-ape crisis, due out next year.

Readers are invited to contribute ideas and talent to the Biosynergy Institute's Bushmeat Project. Write The Bushmeat Project at P. O. Box 488, Hermosa Beach, CA 90254 or e-mail to discuss how you can help.